News

ND businesses, communities slow to embrace EV charging

ND businesses, communities slow to embrace EV charging

Infrastructure plan could offer piggyback opportunities

By Michael Standaert, North Dakota News Cooperative

For most current electric vehicle owners in North Dakota, daily driving isn’t a major issue. Wake up, unplug the car, hop in and head to work, maybe later hit the grocery or take the kids to practice after school and recharge at home in the garage again at night.

Dan Telehey, who commutes 162 miles in his Tesla from Bismarck to Coyote Station power plant near Beulah, is a case in point. The self-proclaimed aficionado of “loud and fast cars” even surprised himself when he went full-EV. Now there’s no going back.

“People think of charging like they think of refueling. If you need gas, you go to the gas station. An EV is not the same in most daily scenarios. You refuel at home while you sleep and in my opinion it is incredibly more convenient than an internal combustion engine car,” Telehey said.

While initial costs of purchasing an EV are high, the time saved by charging at home off electricity, and money saved with zero gas purchases end up paying off in the long run, he said.

“I used to have to fill every other day, or about $60 every two days, when gas was like in-the-toilet cheap. Now that doesn’t exist,” he said.

Traveling further distances on the major interstates for owners living in the main cities is also becoming more convenient, for the most part.

Tesla Superchargers along I-94 in Fargo, Jamestown, Bismarck and Dickinson ensure the ability for Tesla owners to cross the state. Some fast charging options also exist in most of those locations, as well as along I-29, reducing range anxiety for other EV owners.

The biggest drawbacks, they say, are the overall numbers of charging points and the large gaps in rural areas that dissuade or complicate travel. A deeper penetration of charging stations is also needed to offset reduced battery performance during the winter, which can drop as much as 40 percent during the deepest cold.

With the North Dakota Department of Transportation currently finalizing an EV charging infrastructure plan that will largely focus on the buildout of a fast chargers every 50 miles along the two interstates, businesses and communities across the state should be thinking more about lobbying to install their own systems to draw more traffic, and customers, to their communities, EV owners say.

One big hurdle could end up being the price of charging systems. Estimates from the plan indicate costs could be around $900,000 to install four 150 kilowatt fast chargers, or about $225,000 per charger, for those stations along the interstates.

This isn’t necessarily about the 400 or so EV owners currently in North Dakota that make up less than 1 percent of all registered vehicles here, but about travelers coming across the state from elsewhere passing on through if few options exist for fast charging off the beaten path.

It is also about the projected 9 percent of registered vehicles in the state being electric by 2035 and as high as 25 percent by 2045, according to state estimates.

Brian Kopp, from Dickinson, and one of the first EV owners in North Dakota, said the electric vehicle charging system needs to essentially become the equivalent of gas stations, and each location would dictate what the needs are for that area.

“Not everywhere, but every place where there’s more than 100 people,” Kopp said of the need for a charging station. “Richardton [for example] should have one. They don’t need the best one. They don’t need to have five high speed chargers. But they should have two that work for anyone.”

Filling in the gaps

Like Telehey, Sutton Goodman, a coal miner from Hazen, is also not your prototypical Telsa owner.

“I’m the only guy at the coal mine who has one and when I bought it I kinda looked at it like job security,” Goodman said, alluding to the fact that much of the energy used in North Dakota’s grids still comes from coal.

Planning on where to charge becomes a hassle in north and northwest parts of the state, he said. Driving back to his hometown in Upham to visit his mother requires plugging in all weekend before he has enough charge to return to Hazen.

“It’s a pain,” he said.

Despite any inconvenience, Goodman said he still uses his Tesla around 99 percent of the time.

“I like the idea of the car, I like the idea of the Tesla, but for most people, the charging is too much of a drawback,” he said. “If there were more chargers around, people would be more apt to buy an electric car. Until the infrastructure is in place there’s not going to be a whole lot of people buying them, especially if they’re going to be taking them on road trips or long distances.”

Goodman said there is an increased need for “destination chargers” in certain areas, close to other sites or amenities. If Minot placed a few fast chargers downtown, that would draw more people to the city center, he said.

For recent arrival and EV owner Dana Woodruff, the biggest challenge so far seems to be the attitude against more widespread use of electric vehicles and uptake of charging systems by businesses, she said.

In Houston, where Woodruff relocated to Fargo from, she saw exponential growth in the installation of chargers in the past few years as grocery chains, hotels and other businesses began installing them to attract customers.

Initially she had hoped to rent an apartment in Fargo while looking for longer-term accommodation, but instead opted to buy a condo with an individual garage where she could charge her vehicle.

“There were literally no apartment buildings with chargers,” she said. “Not a single one, and that surprised me. There’s exactly one hotel with a charger [in Fargo]. That surprised me because there are plenty of chain hotels here and their locations throughout the country have chargers.”

While similar in that their economies are heavily reliant on fossil fuels, the differences between population centers in Texas and North Dakota when it comes to EVs is like night and day, she said.

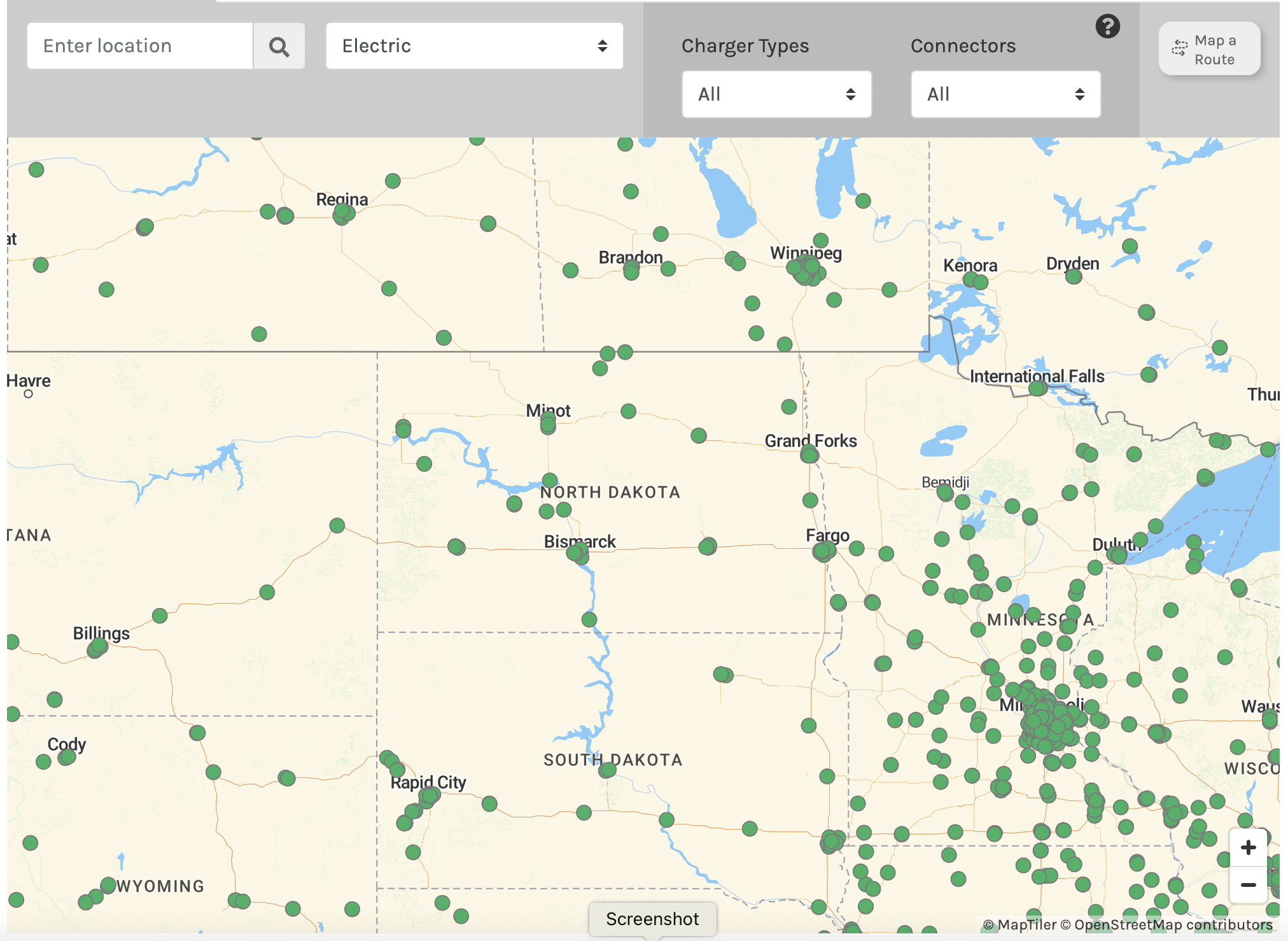

“If you zoom in on the Houston metro area, the thing lights up like a Christmas tree,” Woodruff said, referring to the app PlugShare which shows charging locations. “[But] I wouldn’t be surprised if it did start following the same route [here] where you see more luxury apartment buildings [with chargers], grocery chains, and it starts trickling down.”

Woodruff also suggested installing chargers at state parks, RV parks, certain hotels in more rural locations, and other businesses that host fast charging systems could attract more visitors and customers.

“It wouldn’t need to be a lot, just a handful of chargers in some of these smaller towns near bathrooms and food sources, so that the town can benefit from it too,” Woodruff said.

Some downsides remain

One inescapable fact is the current high price of most EVs. This is largely due to supply chain constraints, inflation and skyrocketing prices of critical raw materials like lithium.

The average price for a brand new EV runs around $66,000 according to Kelley Blue Book, putting them in the luxury range for most buyers.

“We’re still going to need another leap in battery technology before widespread deployment of electric cars is ever going to happen,” Geoff Simon, executive director of the Western Dakota Energy Association, said. “And the price has to come down.”

Another aspect is increased electricity use that could further strain the grid systems.

“The problem with electrifying more of the transportation sector is where are you going to get the electricity, that’s really what this comes down to,” Simon said.

That means reliance on coal will need to continue. Without significant advances in larger scale battery systems to store energy from renewables like solar and wind, grid reliability will remain a headache.

And again, there is a significant loss of range during the coldest months of the year. Most EV owners said they lost around 30 to 40 percent of their battery range during extremely cold weather. Average daily use wouldn’t be as much of an issue, but roaming further afield would.

“So you have about 300 miles range in the summertime, and maybe around 200 in the wintertime, and you’re also going to drain a bit just providing heat in the car,” Simon said. “Then what happens when you get stuck?”