News

Rural communities desperately seeking workers

Rural communities desperately seeking workers

Long-term commitment sought, small-town living offered

By Michael Standaert, North Dakota News Cooperative

Rural communities across the state are desperate to attract and retain workers at small businesses like shops, restaurants, health centers, gas stations and other essential services to keep their communities alive and vibrant.

From Bowman to Bottineau, Crosby to Harvey, they’re also in competition with each other for those workers, not by choice or desire, but out of necessity. Besides attracting labor, communities are becoming more concerned about losing crucial businesses as Baby Boomers retire without adequately establishing a succession plan that keeps business viable.

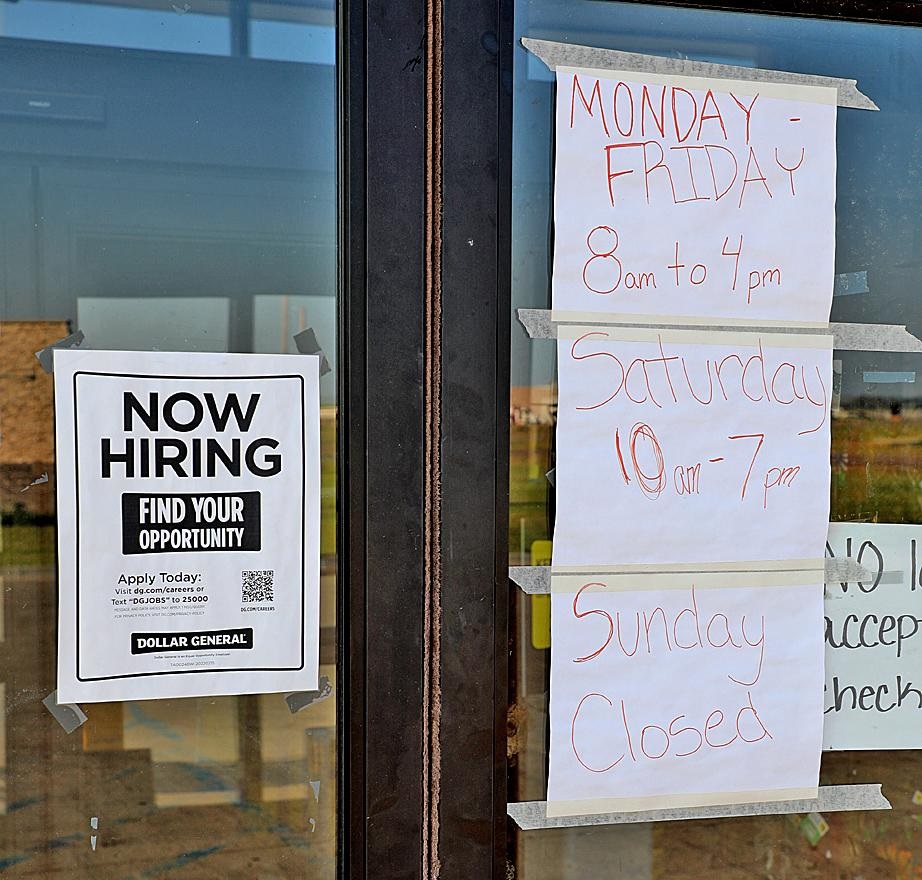

Current workarounds often mean workers pulling double-shifts, restaurants going variable and cutting operating hours, bosses pushing the boundaries of burnout, or for others, shuttering completely.

For Julie Mears, owner of clothing store Golden Rule on Main Street in Bottineau, it means pulling extra duty during shifts she can’t hire for, relying on a staff of mostly teenagers who also often have their own sporadic schedules, and trying to keep things light while managing the variability.

“There’s been a rush on clinical strength deodorant by business owners around the state,” Mears joked between attending to a steady bustle of customers checking out winter coats sales and homecoming outfits.

While not in as dire straits as some businesses, Mears has been impacted by the lack of available labor increasing her own work hours as well as having to be more hands on with younger staff.

It is also a delicate balance when trying to attract new workers from within the community or from nearby towns, since everyone is pretty much in the same boat, she said.

“We really don’t want to be stealing from other communities,” Mears said, echoing similar thoughts by small business owners across the state.

In Harvey, at the B-52 Roadhouse and Lanes, the inability to fully staff the establishment has halted in-restaurant dining during the evening, reducing business by around half, according to owner Chris Kara.

“We have been short-staffed for years, not to this extent, but it has been creeping up to this level for quite some time,” Kara said, adding that he has no applications on his desk so expects hours to remain affected for some time.

He also saw no real possibility of attracting workers from nearby.

“The neighboring communities within reasonable driving distance are small and most of them are already employed,” he said.

Low profit margins, particularly in a small community, and the inability to offer higher pay, medical benefits and other incentives leave restaurants like his particularly vulnerable during labor shortages and when towns are not growing organically.

Without outside help to get to a more equal playing field with larger metro areas, the rural labor shortage will likely persist for some time, with the smallest communities withering, and middling size ones treading water.

“It would be nice if there were more opportunities to support rural communities even more in attracting talent,” said KayCee Lindsey, executive director of the Divide County Job Development Authority in Crosby.

Lindsey noted that the metro areas have a major advantage in professional and financial capacity in conducting campaigns to bring people to their areas that smaller towns, for the most part, do not.

“If we don’t have, you know, a plumber in our community, and these other communities are just as busy, how are we going to get a plumber to come service our community?” Lindsey said as an example of questions some rural communities face as well as concerns over poaching from nearby towns.

According to 2021 data from the US Small Business Administration, small businesses – the majority which have 20 employees or under – in North Dakota accounted for 98.8 percent of all businesses.

Small businesses employed a total of 196,770 people last year, a number that has held somewhat steady in recent years, though there was a net decrease in over 12,000 jobs at smaller operations across the state during that period.

Beautiful, fun loving, enjoys quiet vibes

These businesses are the major economic drivers and employers in most rural areas and important cogs to communities there. Trouble is, larger cities already have a leg up, so economic development officials need to find alternative ways to entice labor into certain areas.

“Everybody talks about the vibe in downtown Fargo. Well, I hate to say it, but there’s not a downtown vibe in Glen Ullin or Gackle or Bowman, right?” Alan Haut, district director for the US Small Business Administration [SBA], said. “There’s a vibe there. It’s a nice peaceful, quiet vibe. But it’s tough to recruit people into those areas.”

Towns like Bowman and Bottineau are trying to change that perception, however.

Instead of chasing big business like some communities did during hydrocarbon boom years, development officials have had to change gears to try to attract new talent to their communities.

“Now economic development has grown to include focuses on quality of life and community development projects, and I think that comes from a state of having to compete for workforce, and knowing that people are not relocating just for the job anymore, but for the community they are in,” said Teran Doerr, executive director of the Bowman County Development Corporation.

For Bowman that means adding a recreational facility, a splash pad for kids to play at, beautification projects and incentives for businesses to upgrade storefronts, she said.

“So our office does the flowers on Main Street, we helped get the trees planted on Main this last year, we are spearheading and helping artists get murals done in downtown here, and we’ve sponsored a grant to encourage art in our community, and that was very popular,” Doerr said. “What we do here is very multifaceted and that’s a lot different from what economic development offices used to be.”

While concentrating on making the town more attractive, Bowman has also initiated grants to companies for tuition assistance, career advancement training, and relocation assistance to address workforce challenges as well as grants for starting or expanding home child care facilities, Doerr said.

To the north in Bottineau, there is a similar refrain, but one that leans toward creating more atmosphere with activities instead of relying on beautification projects.

“Our main focus has been on creating a community that people want to live in, so we do a lot of advertising about what events we have available,” said Whitney Gronitzke, executive director of the Bottineau County Economic Development Corporation.

“We have something going on almost every day event-wise, activity-wise,” Gronitzke said. “Either here on Main Street in the summertime or at Lake Metigoshe.”

Looking for an ongoing relationship

Besides trying to attract workers and professionals to their communities, rural towns are increasingly faced with the challenge of how to replace or continue community-crucial businesses when an owner retires.

“What I’m seeing is that in a lot of these small towns you have a lot of plumbers or electricians, that run their own businesses, and they’re a critical need in those communities, but they’re starting to retire out,” said Haut of the SBA.

For many of these stoic, small town entrepreneurs, thinking about retirement often only comes at the last minute, without much prior thought of how the business could continue in the future under someone else, but there is a real need for such planning for both business people and their communities to transition.

To address this, the SBA along with the North Dakota Small Business Development Centers, Bank of North Dakota and rural banking associations have established a succession planning guide that they are trying to promote in smaller towns.

“So many business owners as they get tired, and get less energy as they get older, and start letting things slide and just maintaining, they find that their business may not be sellable because they haven’t kept it up or got new equipment,” Haut said.

“I’m hopeful that this starts conversations in a lot of these rural communities and hopefully that will set some of these businesses up for a successful transition,” he said.

Lindsey in Divide County has also seen retirements begin to threaten community viability.

In rural areas it is more difficult to quickly sell off a company compared to larger cities where companies often attract a larger clientele and create a valuable brand.

“In this past year I’ve had two businesses that have kind of told me they are ready, and luckily I’ve been able to find someone else [with interest in purchasing] looking at making a career change,” Lindsey said.

“The likelihood of selling a business in six months is not high,” she said. “It typically takes three years to successfully transition a business. You want to make sure that you’re setting yourself up financially, but you also want to be working in conjunction with the local economic development office and the small business center, because they’re going to be the ones that can help find that successor.”

Tagline:

The North Dakota News Cooperative is a new non-profit providing in-depth coverage about North Dakota for North Dakotans. To support local journalism, make your charitable contribution at https://www.newscoopnd.org/

Comments, suggestions, tips? E-mail : michael@newscoopnd.org

Follow us on Twitter @ https://twitter.com/NDNewsCoop

Cutline for photo:

Recent photo of the entrance to Dollar General in Crosby plastered with hand written signs giving notice of variable hours due to a lack of staff. Photo courtesy of Brad Nygaard - The Journal.

Notes:

US Small Business Administration data on 2021: https://cdn.advocacy.sba.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/30121332/Small-Business-Economic-Profile-ND.pdf

And on 2019: https://cdn.advocacy.sba.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/04144123/2020-Small-Business-Economic-Profile-ND.pdf